Using life-centred design to redesign human spaces that also nurture the needs of urban wildlife

Designing fashion and apparel e-retail experiences that challenge binary norms and embrace gender-inclusive UX

Although we’re designers, we learn a lot to incorporate in a design that we pick up in our experiences as consumers. Somewhere around that, we put ourselves in different shoes— of the users, the consumers, the people. It’s where empathy begins. So let me start with a scenario where you and I will step into new shoes.

Picture yourself on a solo shopping date. You step into your favourite clothing store—Zara, Zudio, Westside, The Souled Store, or any other. You take your pick. You walk in, the salesperson greets you, and you ask them for a shirt for yourself. What happens next?

They probably ask you what style, colour, fabric, or size you’re looking for and whether it is for work or casual wear. What happens next?

If I were you, I would most likely be led to the women’s section, where they would show me what’s available.

Let’s pause for a moment here. What was inadvertently assumed in this interaction? Probably that I’m a woman, an assumption based on their perception of my gender presentation, which means- how one perceives my gender based on how I express myself, what I wear, my behaviour, hair, body characteristics, or even voice, and how these align with socially accepted understandings of a given gender.

Categorisation

Such commonly made assumptions often also translate into digital experiences. We see them on e-retail platforms for fashion and apparel when platforms use binary gender options in sign-up forms and feedback surveys, use gendered language, and offer gender-specific product recommendations. Let’s look at some of these.

Here, I have a few screengrabs of commonly known clothing websites. Look at the categories put up by these clothing brands on their e-commerce platforms —

Think of it—before a user, a potential customer, has even scrolled any further than the hero section of the website or app, which is the first thing, the first banner you see, it is already assumed that they will fit into either pronoun; options such as ‘For him’ and ‘For her’ are associated with or rather assumed for men and women, respectively.

In doing so, not only is the pronoun presumed for the user browsing, but it is also arguably an unintentional misgendering that can taint the experience of non-binary and gender-diverse customers from the get-go.

The idea that there are only two genders is called ‘gender binary’ because binary means “having two parts” (in this context, male and female). Therefore, ‘non-binary’ is a term used to describe genders that don’t fall into one of these two categories neatly (transequality.org, n.d). In this piece, I will use the terms ‘non-binary’ and ‘gender diverse’ as umbrella terms.

Uninclusive Language and Options

Before you get to browsing, shopping, or…window shopping on a clothing website, think of the onboarding forms you go over; like login, sign up, and sign in forms. Have you noticed the use of uninclusive language and options in them? The information you fill in the forms is also shown in your profile details.

For instance, in the profile details above, we see the term ‘gender’ has been used. Not only does it stand limited to two options — male and female, they are also sex characteristics and not gender identities.

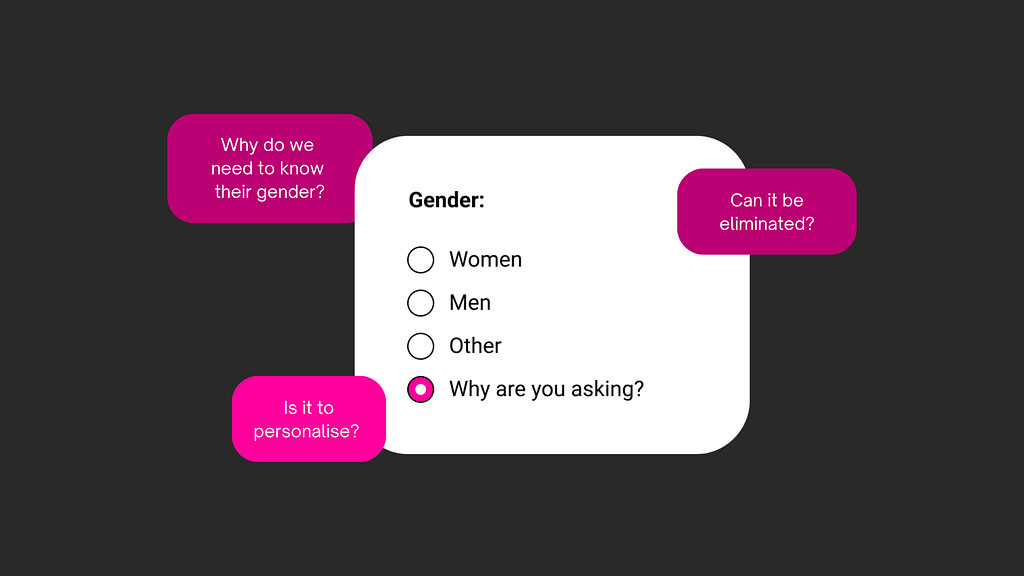

Given these options, I came to some questions-

- How inclusive are they?

- Why do we need them?

- And do we really need them?

The first question is rhetorical, so I’ll skip to the second.

While there are cases, such as medical forms, where it’s necessary to ask for sensitive demographic data, there are many cases where such questions are frivolous. In the fashion industry, asking for gender identity may be needed for a couple of things:

- Personalization: Understanding gender identity can help tailor product recommendations and create a more customized/personalised shopping experience. For example, knowing a user’s preferred gender identity can help suggest styles, fits, and sizes that align with their preferences.

- Inclusive Marketing: It can also aid in inclusive marketing- allowing brands to communicate more effectively and respectfully with their customers by using appropriate language and imagery in marketing materials.

- Product Development: Besides, it can also be helpful in product development; brands can get insights into the diverse identities of their customer base guiding them to develop more inclusive product lines, such as gender-neutral clothing or designs that cater to a wider range of body types and sizes.

So yes, collecting this info may be put to good use, but how much of this data goes towards any of these is often not specified. If we’re going to go about asking for sensitive and personal information, let’s ensure that collecting such data is handled with sensitivity and transparency, clearly explaining why the data is needed and how it will be used to enhance the user experience. Moreover, it is good practice to offer the option to skip or opt out of providing this information to respect user privacy and individual comfort levels.

And do we really need them?

If you answered yes to this, let’s look at the next few examples that could help challenge that notion. (In the interest of challenging ideas over changing minds).

First things first, if it isn’t needed, let’s simply avoid asking.

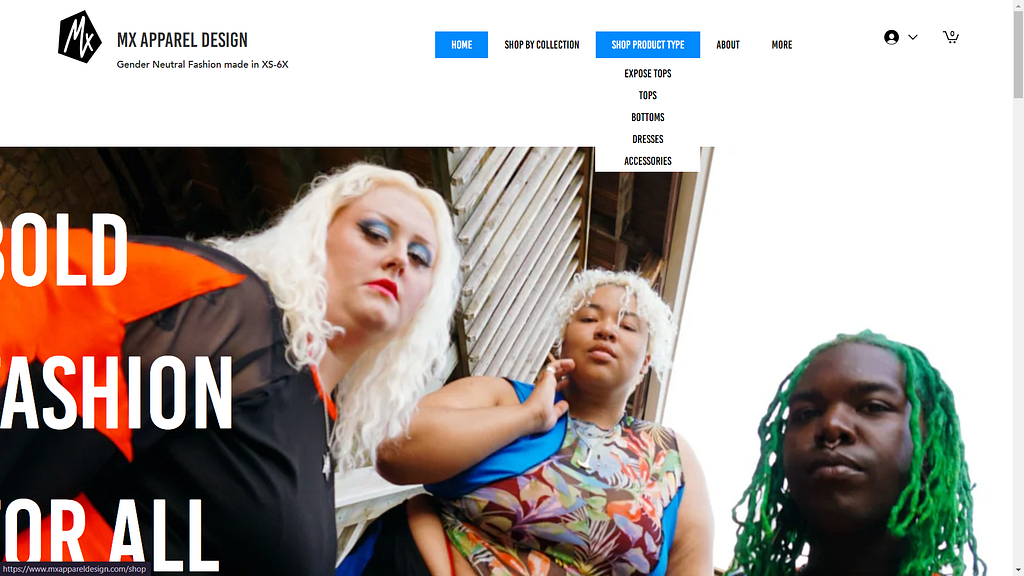

Here’s an example of a clothing brand- Mx Apparel. Above is the form I saw when I first visited the website. The form doesn’t ask for any info on my gender. This is a good example to show that if you don’t need it, sometimes, simply eliminating an ask for unnecessary information can be, in a way, an inclusive practice; especially if personalisation is not a priority. Here’s more on designing gender-inclusive forms (WTTJ Tech, 2022).

I also liked how their navbar exhibits product-based categories, instead of gender-based ones. Like in some examples earlier we saw options that read Shop Men and Shop Women, For Him and For Her. But product-based categorisation as such is an approach that aids in inclusive practices.

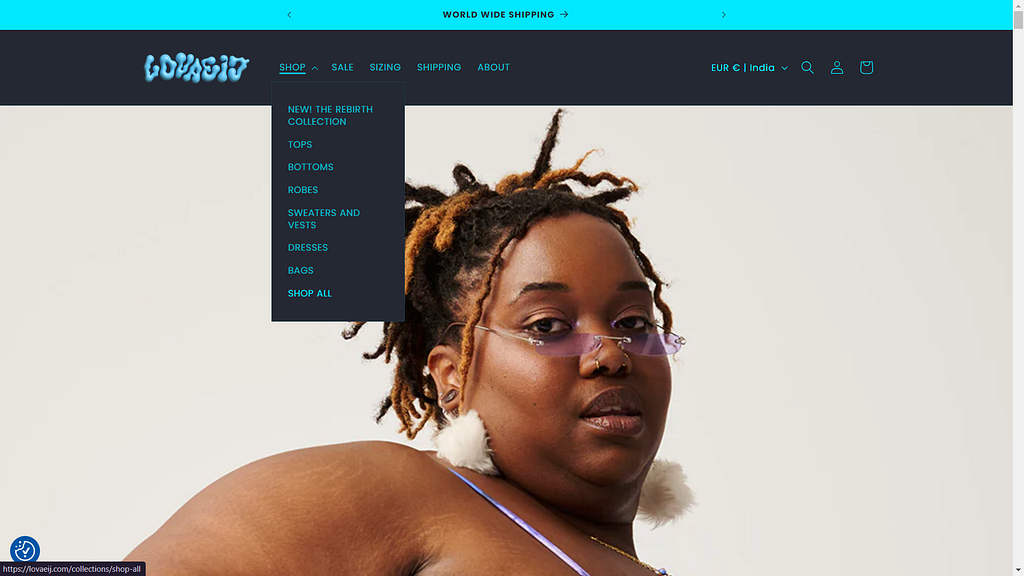

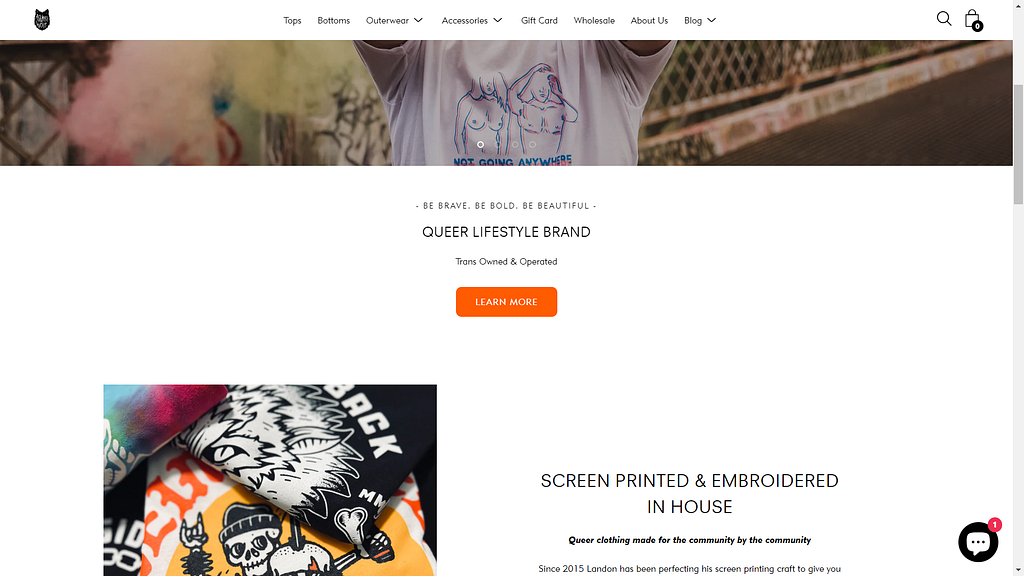

These are some other fashion brands that go with product-based categories.

And here’s an Indian brand that shows size and gender-inclusive representation along with product-based categories.

I like how there’s no assumption of pronouns or limited gender options. — — Mriga Kapadiya and Amrit Kumar, Co-founders of this brand- NorBlack NorWhite, believe that people rarely fall into prescriptive boxes. They exist within the grey, and this notion of the spectrum and a rejection of the binary has led them to create their vivid line and the conceptual thinking behind it (Apparel resources, nd).

As said by former editor at LBB- Sunaina Patnaik —

The best kind of fashion is the one that defies all labels. Fashion is no longer about asking yourself “Is this made for my gender?” or “Can I even wear this?” — in fact, fashion is becoming inclusive, and some Indian labels are spearheading this awesome and revolutionary movement.

As UX designers, we know that we’re not designing something solely for aesthetic appeal but to prioritise better functionality, usability, and experience. We’re not adding a button here randomly or rounding corners because why not? Nope. The bottom line is that we understand that we don’t do something just because; every design decision is made consciously to fulfil a purpose.

That’s where we learn to question; the WHYs. Why do we need to know their gender? Is it to personalise? Can it be eliminated? Can we maybe do an AB test to see which is really working to provide the potential user with a better experience?

If any of this got you thinking, hold that thought- I’ve got more things to add. Let’s look at —

Algorithmic Gender-Bias

Algorithmic gender bias in e-retail platforms occurs when the algorithms that drive product recommendations to you, that target advertisements and search results, reflect and perpetuate gender biases present in the data that they were trained on (economictimes.indiatimes.com, May2024).

A 2021 study by USWITCH, revealed that automated suggestions on predicted text are often gender biased. Uswitch, a comparison and switching service, tested a series of adjectives on smartphones including the Samsung Galaxy S21 and iPhone 12, using this phrase to determine results:

‘You’re a/an *insert word*’.

Of the 236 adjectives tested, 72% suggested a gender-biased response overall. On iOS, almost two-thirds of words generated a male-biased response (Maddyness, July 2021).

Another example is that Princeton University researchers used off-the-shelf machine learning AI software to analyse and link 2.2 million words. They found that the words “woman” and “girl” were more likely to be associated with the arts instead of science and math, which were most likely connected to males*, (*By which I think they meant “men”) (brookings.edu, May 2019).

Let’s observe a similar bias in word associations, but on clothing platforms.

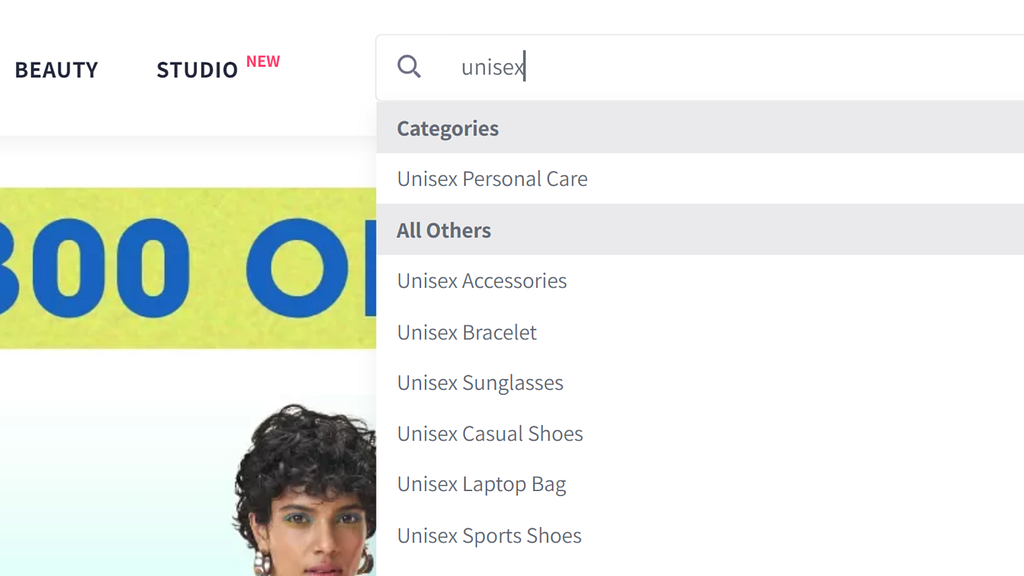

Here’s a screenshot of a search on a popular Indian e-commerce platform for fashion and lifestyle products.

Out of curiosity, I searched for unisex items.

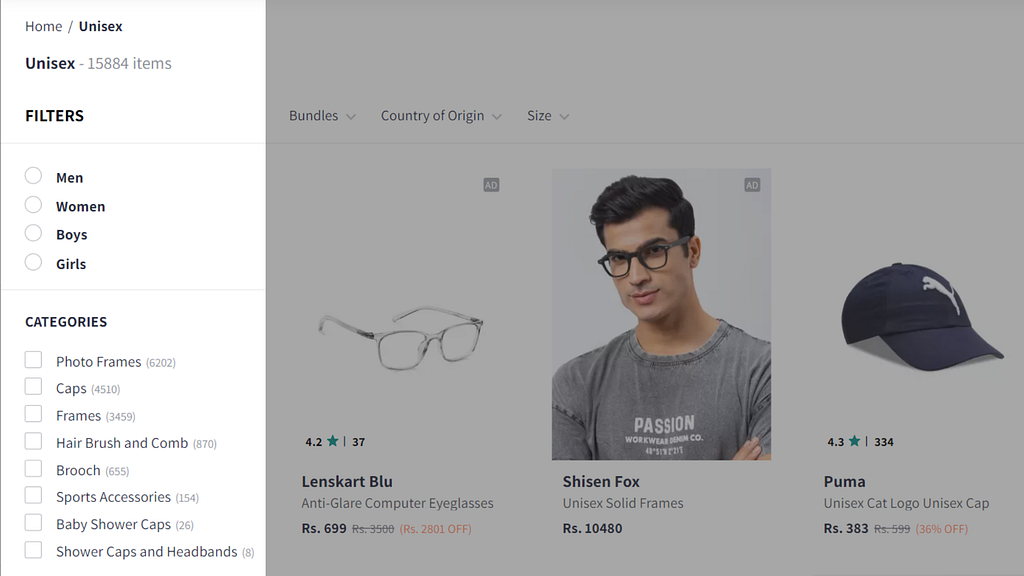

Of the 15,418 items tagged ‘Unisex’- about 4000 are Caps, 20-something are Baby Shower Caps, 8 are Shower Caps and Headbands, but 0 are clothes to put on the body.

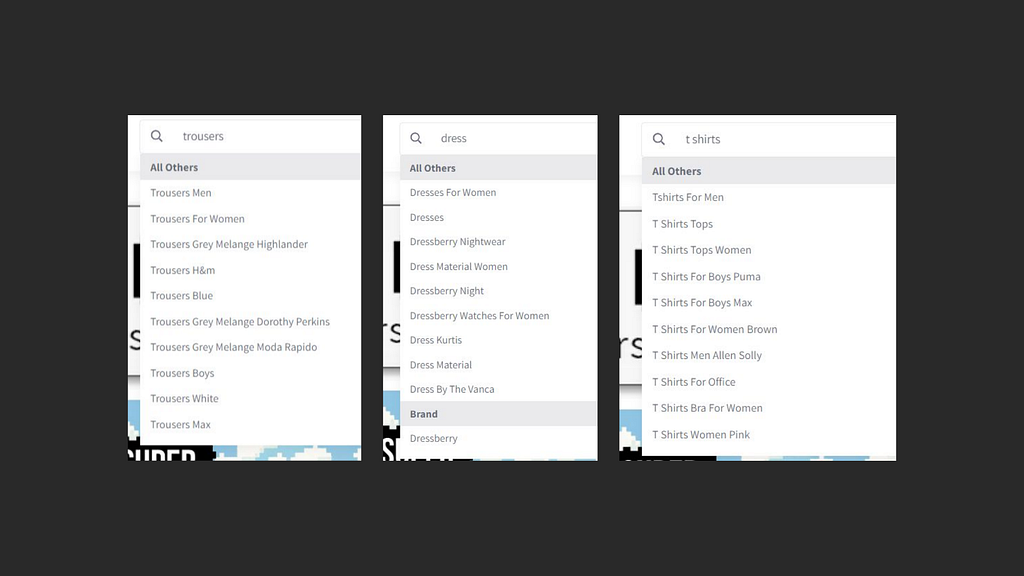

This was out of curiosity. But ‘Unisex’ is probably not a common search, so I went with some commonly searched products; not to see what shows up in the search results, but in the auto-complete predictions.

I searched for trousers, dresses, and T-shirts. It was interesting to see how gendered the auto-complete predictions are:

Note how normalised it is to gender trousers, T-shirts and dresses. How we have ‘Trousers For Women’ and ‘Trousers for Men’, and that its not typically what we would expect to find under anything tagged gender-neutral and/or unisex. How we have 6,844 Photo Frames tagged ‘Unisex’, before 4,057 Caps…but still 0 clothes.

Limiting choice, representation, and inclusivity, such categorisation of commonly used popular online shopping platforms reinforces the gender binary. This often leaves those who identify beyond the binary feeling invisible.

This not only impacts user satisfaction but also limits the potential customer base for businesses; because people buying from Myntra, Amazon, Zara, Ajio, and several other fashion and apparel platforms online aren’t just men and women, or girls and boys, or those who go with he/him and she/her pronouns.

Socio-cultural, Indian and global context:

It’s important to understand the socio-cultural context of where these inherent biases come from.

According to a 2018 report on LGBTQ+ workplace inclusion in the UK by Stonewall, about 31 per cent of non-binary people and 18 per cent of trans people didn’t feel able to wear work attire representing their gender expression (Stonewall, 2018).

From an Indian e-commerce context, (that doesn’t exclusively target a young millennial and GenZ audience), most product marketing advertently or inadvertently reinforces the gender binary. Undoubtedly, a lot of it stems from accepted social norms, and cultural norms; where a binary understanding of gender is prevalent.

Men-women, girls-boys…that’s how we’ve been conditioned to think, and anything beyond that seems out of the ‘norm’, making it harder to comprehend, especially for those who identify within the binary- and/ or probably didn’t see mainstream media representing gender diversity enough. It also makes many of us who identify out of the binary question our feelings.

This, fortunately, is changing. When looking at the Gen-Z age bracket specifically, around 50% of online shoppers globally have purchased fashion outside of their gender identity, and around 70% of consumers say they are interested in buying gender-fluid fashion in the future (Klarna and Dynata, Statista, 22)

While I could gather some global stats on gender-neutral clothing consumption, you must have noticed the lack of relevant data in the Indian context. This is due to the binary format used in official surveys, unfortunately making it difficult to obtain accurate statistics on gender-neutral fashion consumption in India. I do hope that changes.

Speaking of change, and on a brighter note, despite the current data gap, change is underway. I believe that the digital age can be revolutionary in pushing for inclusive design practices. With every passing day, we learn more about our shared experiences with people from the world over; people with diverse backgrounds and cultural environments.

I think it’s a great time to become a designer, to be in the design space, where you and I have a powerful voice, the power to influence, and to do so for the better. I think today, more than ever, we live in a world that is kinder to, more understanding of and more respectful of the experiences of those we find different from ourselves. Having that empathy is what makes us realise that users aren’t merely users of your product, they are people using it. It is that empathy that makes us good designers.

It really is in the little things, you know, that we apply these sensibilities, we acknowledge and accommodate for the new and the previously less talked of things.

Something as small as seeing the they/them option feels validating. Seeing Instagram say- “they’ve replied”, feels good. I’m sitting, scrolling through my feed, thinking that- hey, somebody on their design team has tried to put themselves in my shoes while designing this. They’ve been considerate of and have accounted for my experiences and my preferences. Seeing the pronouns I go with while filling out application forms for jobs feels good.

Making one feel seen and feel heard, can be so validating.

And I think this comes from me being a designer as well as a consumer- that I feel that- that validation shouldn’t be something that feels extraordinary to experience. It should be normal. Inclusivity shouldn’t be an afterthought. Or something that brands suddenly market themselves practising during pride month.

My intention isn’t to call out any of these brands that I took examples from today. They were probably designed by and for a different world they account for. I intend to discuss what we’ve left out while designing these experiences — or rather, WHO we’ve left out, and how we can do better today.

These words by Sr. Product Owner at Adidas, Alexandra Popova, sum up my talk so far beautifully-

Today, the majority of millennials and Gen Z see gender as a spectrum, rather than binary, something that would have been hard to imagine a decade ago. Now, our responsibility as a workplace, business, and part of a community is to reimagine our lives with this new understanding (Contentsquare, 2022).

Practising an inclusive approach in design supports the UN Sustainable Development Goals, such as Gender Equality and Reduced Inequalities. By creating inclusive digital environments, we can promote social and economic inclusion, drive sustainable growth, building a more inclusive e-retail experience for everyone.

We design on the principle of familiarity in UX, right? The Principle of

While seeing binary options may feel familiar because we’re so used to it, we must question what that familiarity rests on. Negligence, perhaps? Overlooking the experience of a significant part of consumers? Must we keep on with it? Why?

One may think- “why complicate things? It’s fine the way it is”. It’s fine for some, but not quite for some alike. And if it feels complicated, simplifying it is our job, isn’t it?

I’d like to leave you with these words by writer Luke Christou:

People want to be seen, heard, and most of all, represented. An authentic understanding of what representation truly means, and how it relates to the struggle for inclusion and diversity, is most likely what fashion can do to be more inclusive (3dlook.ai, 2024).

As a fresh design graduate, right out of the oven, I took to writing thought pieces on sustainable design, diversity, and inclusivity, among other things I enjoy. I’m glad to have had the UXIndia’24 platform to advocate for gender-inclusive design practices with this talk on Gender Inclusive UX in E-retail and engage with gems in the design community.

References:

- Understanding nonbinary people how to be respectful and supportive

- A gradual UX approach to design gender-inclusive forms

- Apparelresources.com

- Algorithms help people see and correct their biases, study shows

- Study reveals gender bias in predictive text algorithms

- Algorithmic bias detection and mitigation: Best practices and policies to reduce consumer harms

- lgbt britain work report- 2018

- U.S. Leads the Way With Gender-Neutral Fashion

- Gender-Inclusivity and Retail: 4 Ways To Build a More Gender-Neutral Brand

- UN_Sustainable Development Goals

- Inclusivity in Fashion

Further Reading:

A Guide To Gender Identity Terms

- SOCIAL MEDIA AS A CATALYST IN MAKING INCLUSIVE FASHION INDUSTRY

- Gender: Why Are You Asking About It?

- Algorithms propagate gender bias in the marketplace — with consumers’ cooperation

She, her, he, and him aren’t the only ones buying clothes was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.