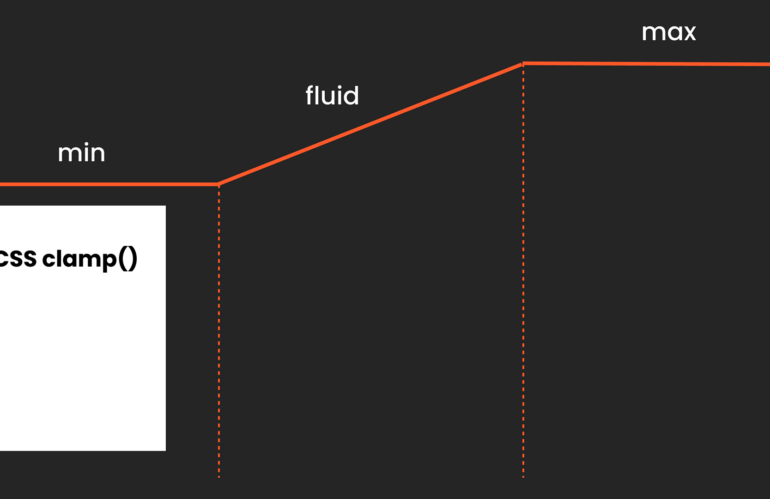

When designing for the web, adaptability is key. Different screen sizes, device orientations, and user preferences must be considered. CSS…

[This is an excerpt of my latest book]

In a recent X/Twitter poll over 200 designers responded to our question about what’s the hardest part of making good design happen:

In first place, with 57.4% of votes, was working with other people. In second place, with 38.4%, was understanding problems, which emphasizes the importance of good user and customer research. In last place, with an astoundingly low 4.2% of votes, was crafing the ideas.

This creates a profound, and frustrating, gap between where our attention is trained to go, craft, and how important decisions actually get made. Typically designers are not decision makers, which means we are advisors more than deciders and are disapointed when we are ignored.

Even if you aren’t frustrated by your career, we’re sure you know many designers who are. These frustrations are more common for design school graduates than for people who learn on their own, but they are common nonetheless. The common reasons designers feel this way include:

- Having your ideas ignored and misunderstood

- Being involved late in important decisions

- Feeling undervalued in your organization

- Needing to explain or justify your role

- Feeling frustrated that powerful people are ignorant about design

- Feeling defeated that nothing ever changes

The first lesson of this book is that these problems are not your fault. You entered this career expecting something better, but you’ve been disappointed. You may have already experienced shock, burnout, and despair. Perhaps you feel limited, held back, and that few coworkers understand you. We call the cause of these feelings the ego trap: the belief that because you are a designer, you should be the creative hero in the story of your organization. If you feel stuck, or you know other designers who feel this way, this trap explains why. This book will teach you how to escape the trap and learn to thrive.

Many designers are in the trap now, or they’ve been in it before. The problem is past generations of designers failed to see the trap and failed to teach us all how to get out of it. We’re sorry this happened. We wish we didn’t have to write this book, but we do. We’re convinced the trap is rampant and self-reinforcing, and it will continue to hurt future generations.

We admit it’s possible we’re wrong about this. Perhaps all designers are flourishing and throwing secret dance parties celebrating their role in late-stage capitalism, and the problem is just that we haven’t been invited. We don’t think so, but if we’re wrong, please invite us!

But if we’re right, then the second lesson of this book is that you must now change something. Expecting the world to change to suit us is not realistic. Instead, we need to have a better mental model for how our work fits into the world. We are designers who create metaphors for our customers, but we desperately need better metaphors for ourselves.

There are three approaches to consider:

A. Seek power. Being undervalued means you do not have the power you need. Who makes decisions you think you should be making? Who doesn’t listen to your advice but really should? Designers need power to design. There’s no way around it. Decisions are really about power, and you need to increase how much power you have.

B. Become influential. If you don’t want the responsibilities that come with power, that’s OK. Instead, become an influencer. Think of your job as a consultant or an advisor, and draw from the rich heritage of skills those roles have always had. If the powerful people you work with listened to you 30% or 50% more ofen, and gave you more credit, would you enjoy your career more? If yes, then influence is the way.

C. Be self-aware. Even without wanting more power or influence, if you can mature your beliefs about design and escape the ego trap, you’ll become a healthier person. Your career will have more flow and be more fulfilling. You’ll get smarter at identifying healthy places to work, or perhaps you’ll realize you want to be your own boss. By becoming self-aware, you’ll be less reactive to the messy reality of human nature in organizations.

This list may scare you. Much of design culture rewards pretending there’s a safer way. We’ve searched, and we don’t think there’s an alternative. If you don’t like these options and prefer to wait for the world to conform to you, we wish you luck, but this book won’t help you. As Anaïs Nin wrote, “It was not the truth they wanted, but an illusion they could bear to live with.” We do not have to accept a bearable life. We are designers, gifed with creative powers few people have. It’s time to use these skills to our advantage and make design easier.

For more from the book Why Design Is Hard, head here.

Why design is hard was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.