Exploring the evolving relationship between humans and AI in product design

Lillian Gilbreth and the two definitions of “Better”

In 1912, at a manufacturing plant in Providence, Rhode Island, two people were watching the same workers but seeing two different things.

Frank Gilbreth stood with a stopwatch, tracking every movement for speed. A turn of the wrist. A step to the left. Every fraction of a second captured in a notebook.

Beside him, Lillian Gilbreth was watching something else entirely. The way a shoulder dropped after lifting too much weight. The shadow on a face straining in low light. The pause before a worker bent down… not to rest, but to reach for a missing tool.

Frank‘s ask was: Could this be faster?

Lillian‘s: Could this be better for the person doing the work?

They were partners in work and in life, but on that factory floor, they were also something else… two definitions of “better,” standing side by side.

I’m Nate Sowder, and this is installment four of unquoted… a series about the people behind the ideas we can’t afford to forget. This is Lillian Gilbreth. You may not know her name, but her inventions and impact are all around your home.

Edited by Pat Hoffmann.

Two definitions of better

Frank’s definition was simple: better meant faster. A shorter reach, a smaller motion, a task shaved down to its most efficient form.

Lillian’s definition was different: better meant the work fit the worker. The lighting didn’t strain your eyes, and the day didn’t leave you feeling smaller than when it started, let alone, wreck your back.

“Psychology of Management, as here used, means, the effect of the mind that is directing work upon that work which is directed, and the effect of this undirected and directed work upon the mind of the worker.”

— The Psychology of Management (1914)

Together, they built systems that were more durable than either of their views alone. Speed without satisfaction was brittle, cracking under stress. Satisfaction without speed was irrelevant. It couldn’t compete. Holding to both meant building something that could last.

When Frank died suddenly in 1924, many of their clients dropped off… not because the work had lost value, but because factories rarely hired women engineers. Lillian had to reframe her work on her own terms.

A wider field

Gilbreth turned her attention away from manufacturing and toward spaces where her expertise would be hard to dismiss: hospitals, kitchens and schools.

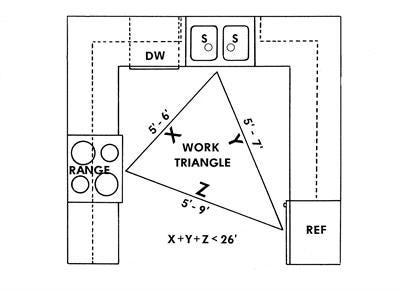

She applied the same thinking she’d brought to the factory floor, but with more than a stopwatch. She set up cameras to film work as it happened, then broke those movements into “therbligs” (Gilbreth spelled backward)… the 18 elemental motions she and Frank had named and catalogued.

In one hospital project, she filmed surgeons and nurses mid-operation, recording each reach, pivot and step. The footage revealed wasted motions invisible to the naked eye which caused Lillian to reorganize the surgical field so instruments landed exactly where hands expected them, cutting thousands of unnecessary movements from procedures.

And while those films now rest in dusty reels and library drawers, her work lives on in kitchens and classrooms, offices and operations. Lillian Gilbreth is responsible for shelves in refrigerator doors, the foot pedal trash can, and kitchen counters set at the right height for comfort… rather than convention.

With twelve children, her home doubled as a laboratory. Those experiments became the basis for Cheaper by the Dozen… first a bestselling memoir, then a 1950 film. Millions laughed at the fictionalized family, never realizing the real one had redesigned everyday life.

Her work carried her into government consulting during the Depression and World War II. In 1935, she became the first female professor at Purdue University’s School of Engineering, teaching a generation of engineers to think about people as more than parts in a process.

“The things which concerned him (Frank) more than anything else were the what and the why… the depth type of thinking which showed you the reason for doing the thing and would perhaps indicate clearly whether you should… change what was being done.”

— Lillian M. Gilbreth, Delivered at the American Institute of Industrial Engineers conference.

By the end of her career, her fingerprints were everywhere: in homes, in hospitals, in workplaces. She had merged psychology with engineering decades before “human factors” was a recognized field, earning honorary membership in the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and becoming the first woman to teach in Purdue’s School of Engineering.

In 1984, the U.S. Postal Service put her in the Great Americans series — one of the first psychologists honored on a U.S. stamp.

The Gilbreth test — for AI, design, and strategy

On the factory floor, Frank focused on outcomes: the goal, the task, the work that needed to be optimized.

Lillian focused on context and intent: the environment, the constraints, the human reality shaping the work.

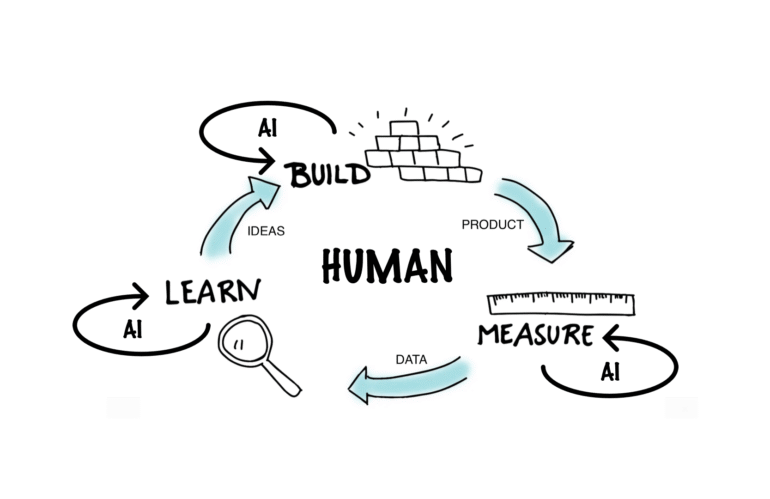

When we work with AI, most of us are like Frank.

We hand AI a task… “Summarize this,” “Write that,” “Give me five ideas” — without giving it the surrounding context or intent it needs.

In user research, the same trap shows up as feature-driven interviews instead of situational ones. We ask, “Would you use this?” without asking, “What’s going on around you when you would?”

Lillian’s approach works as a two-part check for both:

- State the intent — the “what.” Define it so clearly the system or person can’t miss the target.

- Build the context — the “why.” Map the constraints, conditions and background that shape how the goal is reached. Without it, the output might be fast… but it won’t hold up.

AI without intent is aimless.

AI without context is weak.

Lillian’s genius was keeping tight to both. Not just making work faster, but making it fit the worker. In AI, that’s the difference between a model that completes a task and one that meaningfully moves your work forward.

Taking Lillian’s approach of using context and intent is simple.

Try this

Instead of giving AI a task, give it your problem. Write it out as if you were explaining it to someone who can’t see what you see. Include what you’re trying to achieve, why it matters and what’s in the way.

Example prompt:

I’m trying to reduce the time it takes for our support team to resolve billing errors. The challenge is that the data is in multiple systems, and customers often send incomplete information. I want ideas that help us fix errors faster without adding work for the customer. Can you help me think through this?

The act of framing the problem will force you to surface intent, context and constraints.

That’s how Lillian worked: she made the problem visible before she tried to solve it.

Back to the factory floor

In 1912, Lillian stood beside Frank on that factory floor in Providence. Two people, two lenses, one question: what does it mean to make something better?

Frank watched the clock.

Lillian watched the people.

Together, they produced something more durable than either could alone. And when she was left to carry that work forward, she made sure it didn’t just get faster… it got better.

The stopwatch told you how quickly the work could be done.

Lillian told you how the work could be done without breaking the person doing it.

This is unquoted… a series about the people behind the ideas we can’t afford to forget.

Next week: the mathematician who predicted our future… and warned us about it, decades before anyone listened.

What the stopwatch missed was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.